Guardian article written by Simon Reeve about the Meet the Stan series:

AS THE headless corpse of the goat began to slip out

from under my leg I realised I had neither the stomach

nor the skill to play the legendary Central Asian game

of Kokpar on horseback in Kazakhstan.

I had been forced onto a horse and into the game, best

described as something akin to bloody polo, by a

village elder after pausing to see a traditional

baby-naming ceremony. It was supposed to be a brief

stop on the road to Almaty, the main city in

Kazakhstan. But the entire village turned out to watch,

so I took a deep breath, grabbed at the goat’s

mangled testicles to keep it from slipping to the

ground, urged my horse forward, and was rewarded with

an invitation to the village feast. I just wish I could

have washed my hands before eating bits of goat with my

fingers.

Generous hospitality is legendary in Central Asia, and

woe betide anyone thinking of spurning a proffered

glass of vodka, or a week-old piece of goat meat, as I

discovered on a long journey through ‘the

Stans’ (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and

Uzbekistan) with a BBC television crew for the

documentary series ‘Meet the Stans’.

After writing a book on Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda in

the late 1990s, I had long been fascinated by this

forgotten corner of the world, where Islamic militancy

is on the rise, and which I fear could be a potential

future flashpoint and focus for the ‘war on

terror’.

The Stans were a backwater of the Soviet Union until

the country collapsed in 1991. Independence and the

discovery of the world’s largest untapped energy

reserves has barely raised their profile. Central Asia

is a vast area bigger than Western Europe, but it

remains perhaps the most obscure region on Earth.

We began our journey in the far north-west of

Kazakhstan, by the Russian border, and travelled by

plane, train, helicopter and 4WD east across the

endless Kazakh steppes to the Chinese border, then

south through little Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the

Afghan border, and west through Uzbekistan to the

ancient Silk Road cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.

The region was fascinating and bizarre in equal

measures. One of our first stops was the dry bed of the

contaminated Aral Sea. Formerly the world’s

fourth largest inland lake it has shrunk to half its

size since the Soviets diverted rivers to irrigate

cotton fields.

Local fishermen have started breeding camels while

their huge boats rust and rot. My attempts to fend off

one of their amorous camels were successful; not so my

attempts to avoid downing fermenting camel’s milk

and most of a bottle of vodka early in the morning.

Heading east across Kazakhstan, with a brief stop for

my game of Kokpar, our 4WD suffered a steady series of

punctures on the potholed roads. Our record was four in

one day. The nights are cold on the Kazakh steppes, and

none more so than when we suffered a flat at 11pm one

night 100 miles from a depressed little town called

Kyzylorda. We walked through the darkness to a police

checkpoint and hitched a ride for a 2am audience with

the Kazakh Beatles, a tribute band who suffered years

of state harassment during Communist rule.

Further east on the road to Almaty, the main city, we

visited a biological weapons laboratory abandoned by

the Soviets. Underpaid scientists in what is now

described as a ‘plague research institute’

showed me vials of anthrax and plague stored in

tupperware jars in old fridges. Security against attack

by committed terrorists seeking biological agents

weapons was woefully inadequate.

Almaty offered more surprises. Parochial and glamorous

in equal measures, it offers plenty of late-night

diversions. Taking the road south into Kyrgyzstan, we

found an Islamic militant threatening to martyr himself

against the West, visited a contaminated radioactive

waste dump, and talked our way onto a US-led coalition

airbase in the former Soviet Union. Mountainous and

beautiful, Kyrgyzstan offers fantastic trekking, if

only people could find it on the map.

A wizened farmer on a donkey cart took me across the

border into Tajikistan, the poorest state in the former

Soviet Union, where up to 150,000 died during civil war

in the 1990s. They don’t get many visitors in

Tajikistan, and the country has the worst accommodation

in the region.

Tajik doctors and government officials earn between

£3-£5 a month, and corruption is a major problem. We

had agreed to stay in a foreign ministry

official’s home in Dushanbe, the capital. At

first sight it was bad enough, with mould, windowless

rooms, and damp, smelly mattresses. As I stood at the

sink waiting for the water to turn from brown to clear,

idly watching two cockroaches scuttling along the

filthy floor, I nearly trod on a colossal brick-sized

rat-trap, primed with a chunk of rancid cheese.

Tajikistan has become a major transit route for heroin

from Afghanistan. It shares an 800-mile border with the

war-torn state, which supplies 90 per cent of European

heroin. I followed the police on a raid in Dushanbe and

watched as they caught a mother of six with a kilo and

a half. The police just shrugged, and showed me a store

containing half a ton.

With a Colonel from the Tajik Secret Police in tow we

drove down to the Afghan border, which is guarded by

19-year-old Tajik conscripts living off bits of bread

and old potatoes. Despite empty cupboards, the border

guards arranged a minor feast for us with a tin of

pilchards.

We had been told to leave the border region before dark

and quietly because of militants and armed Taliban

sympathisers. But as the sun set the vodka emerged.

Eight large bowls later I was pouring drink into my

sock to avoid an early demise. We left after midnight

singing out of the open windows of our 4WD.

Chugging back from the border along Tajikistan’s

horrendous roads, we met the country’s top pop

star, a 22-year-old ex-Etonian called Wills who runs

his Canadian father’s gold mine, and a former

warlord. Tajikistan has a laid back Wild West feel. I

loved the place.

By contrast Uzbekistan, our next stop, reeks of

oppression. Thousands have been jailed as the

government cracks down on dissent and Islamic

militancy. Uzbeks are sick of their leadership and its

bizarre laws. Late one night, I crept around the back

of a gutted shop in Tashkent, the capital, and broke

Uzbek law by entering a pool hall to play a few games.

Snooker and pool were banned last October. Gossips

claim the son of a Presidential aide lost a fortune on

a game, and his father banned the sport in a fit of

pique.

But despite its problems, Uzbekistan, like the whole of

Central Asia, remains a joy to visit. In legendary

Samarkand and Bukhara, the holiest city in Central

Asia, we found Islamic architecture on a par with the

finest in the world. In Bukhara near the end of our

journey, I stood in a mosque courtyard near the base of

the 800-year-old Kalon minaret as the muezzin chanted

the haunting call to prayer. The experience, which

banished my exhaustion, was one I cherish to this day.

Simon Reeve, 2003.

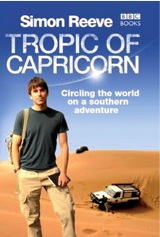

Simon Reeve is the author of The New Jackals: Ramzi

Yousef, Osama bin Laden and the future of terrorism,

and the presenter of ‘Meet the Stans’, to

be broadcast on BBC4 on September 29th and 30th at 9pm,

and on BBC2 later this year.

________________________________________

Buy Simon's latest book from here via Amazon:

Details of Simon's books:

The New Jackals: Ramzi Yousef, Osama bin Laden and the future of terrorism

and also here

One Day in September: the full story of the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre and Israeli revenge operation 'Wrath of God'

Details of Simon's TV Travels:

Equator - a long journey around the warm waistband of the planet

Places That Don't Exist - a series of adventures in countries that aren't officially countries

Meet the Stans - Simon's long journey around Central Asia

For those interested, here's a biography of Simon

And some photos

Home l

Books l

TV l

Articles l

Contact l

Questions? l

Biography

see the award-winning

photography of James Reeve, Simon's brother,

here

![]()

Disclaimer: The

information on this website was as accurate as possible

when it was written, but situations change. We accept no

responsibility for any loss, injury or inconvenience

sustained by anyone resulting from this information. You

should conduct your own research before traveling abroad

and check for the latest information on critical issues

such as security, visas, health and safety, customs, and

transportation with the relevant authorities before you

leave.