This four-part series, shown in 2003 on BBC2, BBC World and by broadcasters internationally, took Simon Reeve from the far north-west of Kazakhstan, by the Russian border, east to the Chinese border, south through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the edge of Afghanistan, and west to Uzbekistan and the legendary Silk Road cities of Samarkand and Bukhara.

_________________________________________________

Press release issued by Canadian broadcaster CBC about the series:

TRAVEL TO CENTRAL ASIA TO “MEET THE STANS” IN A

CBC NEWS: CORRESPONDENT SPECIAL SERIES

DEC. 20 TO 23 AT 8 P.M. ET / PT ON CBC NEWSWORLD

As part of its holiday programming, CBC Newsworld features an insightful and entertaining four-part BBC series, Holidays in the Danger Zone: Meet the Stans. This special presentation of CBC NEWS: CORRESPONDENT airs Dec. 20 to 23 at 8 p.m. ET and 8 p.m. PT.

In this series, journalist Simon Reeve travels to Central Asia to “meet the Stans” - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan His journey provides viewers with a unique insight into these countries’culture and politics. As well as discovering a region teeming with Islamic militants, ruthless tyrants and radioactive wastelands, Reeve also finds a more absurd side to these obscure countries, including an American military base that sells Soviet knickknacks, a desert full of shipwrecks and a first-rate Beatles tribute band.

Holidays in the Danger Zone: Meet the Stans begins on Monday, Dec. 20 at 8 p.m. ET/PT in Kazakhstan, a country whose oil deposits are thought to rival those of Saudi Arabia. In Kazakhstan, Reeve discovers a poorly secured former biological weapons factories with a hundred types of plague stored there. He also finds a shrinking sea that is now home to camel farmers, and the region's best Beatles tribute band.

On Tuesday, Dec. 21 at 8 p.m. ET/PT, part two of the series features Kyrgyzstan, the only country in the world with both an American and a Russian military base. While there, Reeve meets a member of a banned radical Islamic group, and he visits one of the world's most highly radioactive sites.

In Uzbekistan, the most repressive of the "Stans", Reeve finds himself followed by the secret police as he travels across the country. He also meets the country's most famous pop star, visits a bodyguard training school, breaks the law by playing snooker, and meets women at a marriage bureau for Uzbeks wanting western husbands. His adventures in Uzbekistan air Wednesday, Dec. 22 at 8 p.m. ET/PT.

The final episode features Tajikistan on Thursday, Dec. 23 at 8 p.m. ET/PT. Sharing an 800-mile border with Afghanistan, which provides 90% of Europe's heroin, Tajikistan is one of the world's biggest drug trafficking routes. Reeve joins a drugs raid, visits a warehouse with £100 million worth of heroin, and gets drunk with the conscripts who patrol the Afghan border.

(The fifth “Stan” Turkmenistan, refused Reeve and his BBC crew a visit to their country)

Holidays in the Danger Zone: Meet the Stans is a BBC production. The senior producer for CBC NEWS: CORRESPONDENT is Jet Belgraver.

_________________________________________________

Article written by Simon about his travels:

The Sunday Telegraph Travel Section

September 2003

THE CALL OF THE STEPPES

Uzbekistan and its neighbours have long fascinated Simon Reeve

The two armed Kazakh policemen on the train were curious. "So what is your impression of Central Asia, and is it what you expected?" they asked, surprised to see a Westerner journeying across the endless flat steppes of Kazakhstan.

The previous day I had missed the train heading east from Aktobe, in the far north-west of Kazakhstan, to Almaty (Alma-Ata), the main city, because it left half an hour early. Now I was on a train that did not appear on any official timetable. I only managed to get a ticket when Bayan, my tenacious Kazakh guide, ejected the local mayor from his bed and forced him to call, still in his pyjamas, on the rail commissar.

I stumbled over my reply to my new friends, unsure how to tell them I was already finding Central Asia wonderfully eccentric. So instead we swapped stories about growing up on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain, and I settled back on the first leg of my trip through "the Stans" (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan; journalists are not allowed into Turkmenistan) with a BBC television crew for the documentary series Holidays in the Danger Zone.

Since writing a book on al-Qaeda in the late 1990s, I have been fascinated by this forgotten corner of the world, which I fear could be a potential future flashpoint in the "war on terror". Despite this, Central Asia, a region bigger than Western Europe, has much more to offer than a problem with Islamic militancy.

Apart from some of the finest Islamic architecture in the world, there is also the ancient Silk Road, which winds its way through the Stans, lending an extra air of mystery to magical cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand. Nature also blesses the region with spectacular scenery untouched by tourism or development. Nowhere is this more true than the Charyn Canyon, a few hours east of Almaty, which I finally reached after travelling by plane, train, horse and helicopter across Kazakhstan. Marat, our driver, a former Soviet police captain and winner of the Kazakh Who Wants to be a Millionaire? TV show, took us to the floor of the canyon in his four-wheel drive, past mansion-sized chunks of rock perched precariously over the track. I held my breath as we passed. Second only to the Grand Canyon in scale, I found Charyn more impressive due to the absence of other visitors.

The canyon is a perfect metaphor for the entire region: vast, unspoilt and completely unknown. Before 1991 the Stans were a backwater of the Soviet Union, and the canyon's proximity to the Chinese border rendered it off-limits even to Kazakhs. It did not appear on maps, and many Kazakhs are still unaware it exists.

Our plan was to head south from the canyon, but the road took us back to Almaty, and a night on the tiles that again confounded expectations. Late dinner was followed by drinks in a bar called Heaven, which shared the design aesthetics of a counterpart in London or New York, but was empty when I arrived at 11.30 with the BBC's Will Daws and Dimitri Collingridge. The only other foreigners were a couple of young Australians in town to sell tennis nets, and together we bemoaned the $10 entry fee, a month's wage for most in Central Asia, until the upstairs dance floor opened at midnight, and the club began to fill with a collection of the most glamorous women (and men) I have seen.

The next morning, with sore heads we took the road south from Almaty into Kyrgyzstan, a land of gorgeous meadows and jagged peaks. The Kyrgyz government hopes to attract adventure tourists seeking whitewater rafting and mountain trekking, but the country has barely a notion of a tourist infrastructure.

"Diplomats, VIPs, and beezneez elite," he replied.

"What exactly does business elite mean?" I asked naively.

"Beezneez elite means beezneez elite," he replied with an enigmatic smile.

Organised crime is certainly a problem in Central Asia, but not for visitors. Local criminals are more interested in the rich pickings garnered from shipping heroin from Afghanistan to Russia and Europe.

We drove to Bishkek, the sleepy Kyrgyz capital, and a Hyatt hotel full of American Special Forces on leave from Afghanistan. While they lounged in the hotel's casino, we headed for the national museum, an eccentric celebration of the Soviet past.

The casino now happily accepts the US dollar, but murals in the museum portrayed evil Americans, one of whom resembled George Bush, sitting astride nuclear missiles and laying waste to legions of defenceless women and children. Outside, teenagers asked in English if I liked ganja before skating off around the base of a statue of Lenin, still standing proudly in the main square. "We're quite tolerant of Soviet history," said Kadyr, my young guide. "Many people think life was better under Communism."

It was easy to understand why when I headed south again and, on a donkey cart, crossed into Tajikistan, Afghanistan's mountainous northern neighbour. Now the poorest and most lawless of the countries in Central Asia, Tajikistan's economy is still reeling after civil war in the 1990s killed up to 150,000. At least 80 per cent of the population lives in poverty and wages are as low as £3 a month. Burned-out Soviet factories litter the landscape, and gasoline is sold in jars by the side of the road. "Life was never this bad under the Soviets," was a constant refrain.

Tourism is virtually non-existent in Tajikistan. The only foreigners I saw were aid workers or businessmen investing in high-risk ventures. But the country is getting back on its feet, and streets that resounded with gunfire just a few years ago now host outdoor cafes and promenading couples. Tajikistan has a long way to go, but I loved the place. The Tajiks were friendly, generous, hospitable and devoid of obvious envy, even when a couple of them debating our salaries asked, wide-eyed, whether we earned more than $10,000 a day.

Of course, for tourists seeking an entirely different cultural experience, the isolation of Central Asia is part of the appeal. Almaty and Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, now host a few Western shops, but the rest of the region has been forgotten by Western businesses. Yet we ignore Central Asia at our peril. Economic growth would be a useful bulwark against growing political discontent and emerging militant groups that agitate against both the authoritarian regimes in the Stans and the West for supporting their oppressive leaders.

Geographically the Stans are closer to India and the east, to which they look for cultural leadership just as much as they look to Mother Russia or the West. At a celebration of the end of the civil war in Dushanbe, teenagers queued to take photographs with ancient cameras next to cardboard cut-outs of Bollywood - not Hollywood - stars.

Music is also largely free of Western influences in the Stans, where most people seem to prefer traditional songs. In Dushanbe, Gurminj Zawkibekov, a wizened former Soviet actor who tops the Tajik charts, gave me a recital of the haunting sounds of the remote Pamir region. His band has seen record sales soar since the Soviet Union collapsed and Tajiks began to rediscover their heritage.

To the accompaniment of one of Gurminj's CDs, we drove south through glorious countryside to the Afghan border, a route best avoided unless accompanied by an armed colonel from the Tajik secret police and a detachment of border guards. The border is still bandit country. We lingered briefly, before heading west into Uzbekistan.

Samarkand was a joy. It is graced by the breathtaking Registan, a three-sided square and perhaps the finest built space in the Islamic world. We bribed a policeman and climbed a secret passage hidden behind a carpet store to the top of one of the minarets.

For years I had longed to visit the ancient Silk Road city of Bukhara. I was excited as we drew close to it, but the motion of our four-wheel drive bumping along the road sent me to sleep. The sound of a huge wooden door creaking open finally roused me as we parked, late at night, outside a guesthouse in Bukhara. I picked myself off the floor of the van, where half my body had slumped as I slept, rubbed my bleary eyes, and peered out of the back of the van window, at one of the most evocative sights I have ever seen.

The guesthouse was next to the glowing domes of the majestic 16th-century Mir-i-Arab Madrasa, an Islamic college. Light streamed from tiny windows sparkling along its colossal wall like portholes in a ship, and danced over striking blue tiles thought to derive their unique colour from a mix of human blood. To the side of the madrasa was the chubby base of the legendary Kalon minaret, an elegant mosque tower built in 1187 to call the faithful to prayer, and for centuries lit by fires to guide camel trains travelling through the night. Although Genghis Khan destroyed Bukhara in 1220, he gazed in awe at the Kalon minaret and ordered it spared, thereby enabling more recent rulers to execute victims and criminals by throwing them off the top.

An ethereal golden glow from oil lamps and elegant lights played over the brickwork as my eyes widened and traced the minaret 160ft into the dark sky, just as the haunting sound of an Islamic prayer rehearsal drifted from the madrasa towards our hotel. I was nearing the end of my journey through this wonderful region, and I scrambled out of the van to gasp at the medieval vision. It was so beautiful that even as I remember the sight now a lump rises in my throat. One day, I hope to return.

CENTRAL ASIA BASICS

Getting there

The easiest way to travel through Central Asia is with a tour group. Regent Holidays (0117 921 1711; www.regent-holidays.co.uk) offers a nine-day Kyrgyz Explorer trip, a 14-day Uzbekistan Encounter and an eight-day Kazak Explorer trip from £591-£989, excluding international flights. Dragoman (01728 861133; www.dragoman.com) offers a variety of overland trips through Central Asia. Silk Steps (01454 888850; www.silksteps.co.uk) runs tours to the region, while Explore Worldwide (01252 760100; www.explore-worldwide.com) has a 10-day Golden Road to Samarkand tour (also visiting Tashkent, Bukhara and Khiva) from £1,025, including flights.

Staying there

There are good Western hotels in the main cities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, including a Hyatt Regency in Almaty and Bishkek (0845 888 1226; www.hyatt.com), and an InterContinental in Tashkent (08000 289387; www.intercontinental.com). Tajikistan is sorely lacking in decent hotels and any real tourist infrastructure: rooms on the top floor of the Hotel Tajikistan in Dushanbe are passable, but often reserved for diplomats and drug lords.

Eating out

Be wary. Most food is fresh, organic and healthy, but meat is often left lying around. If given the option again I would avoid fermenting camel's milk, particularly when drunk under the watchful eye of a hairy camel breeder, and sour yoghurt balls made from goat's milk, which I loathed.

When to go

September to early November and May to early June; at other times, the region is too hot or too cold.

Security update

The Foreign Office says most visits to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan are trouble-free but there is the "potential for terrorist attacks by international groups". Visitors to Kyrgyzstan are warned to avoid the area around Osh close to the Uzbek border. Muggings are thought to a particular problem in Kyrgyzstan, but I encountered no real problems or animosity in the region. The FCO is less keen for tourists to visit Tajikistan and advises against non-essential travel in mountains and valleys of central Tajikistan. For further advice, visit the FCO website (www.fco.gov.uk).

_________________________________________________

Links:

Buying this series on DVD

Simon's Guardian article about the series

BBC article about the series

Series photos on Facebook

_________________________________________________

Another article about Meet the Stans -- written by Simon for the Canadian CBC website for the series:

By Simon Reeve

THE underpaid scientist opens the fridge door and pulls

out a tupperware jar containing vials of anthrax for me

to inspect. Behind us a row of ancient refrigerators

contain vast quantities of plague. The scientist pulls

out a tray of diseases, then accidentally whacks the

fragile glass vials as she puts them away. One of her

colleagues gasps in fear. Everybody in the room

freezes. Nobody dares to breathe.

Welcome to a former Soviet biological weapons

laboratory in Kazakhstan, abandoned by Moscow when the

USSR collapsed in 1991, and now a Plague Research

Institute. I was visiting the lab during a long journey

through Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and

Kyrgyzstan, collectively known as the Central Asian

‘Stans’, with a BBC television crew for a

four-part documentary series. It was an extraordinary

tour of a beautiful, bizarre and unpredictable region.

Although Central Asia is larger than Western Europe, it

is probably the most obscure area of the world. A

glance at an atlas suggests no area of comparable size

about which so little is known in the West. Because we

know little about the Stans, we care little about their

problems. Yet we should pay Central Asia more

attention, because this is a region that matters to the

West.

In the late 1990s I wrote a book on bin Laden and al

Qaeda which warned the group was becoming a global

threat. In the aftermath of September 11th, I believe

Central Asia, a region afflicted by poverty, corruption

and despotic regimes, could be a future flashpoint for

the ‘war on terror’.

Our Central Asian journey began in the far north-west

of Kazakhstan, by the Russian border. We travelled by

plane, train, helicopter, horse and 4WD east across the

vast Kazakh steppes to the Chinese border, then south

through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the Afghan border,

and west through Uzbekistan to the ancient Silk Road

cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.

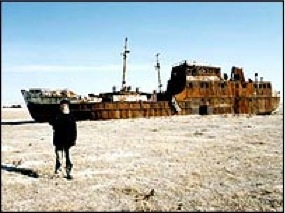

Central Asia was a remote corner of the Soviet Union

before it collapsed in 1991, and the Soviets left a

painful legacy. In the west of Kazakhstan fishing boats

sit rusting on the dry bed of the Aral Sea, which used

to be the fourth-largest inland lake in the world until

Soviet planners pumped chemicals into the sea and

deliberately diverted rivers to irrigate thirsty cotton

fields.

The Soviet legacy also includes radioactive waste

dumps, which are scattered across the region. In

Kyrgyzstan I visited several which have contaminated

local villages and threaten an environmental

catastrophe if they flood, or a terrorist threat if

their contents are plundered for a radioactive

‘dirty’ bomb. Wearing chemical and

biological protection suits to guard against

radioactive particles, and hoping we were avoiding

‘hot-spots’ where radiation spiked to more

than 1,000 times normal levels, BBC Producer Will Daws

and I chanced upon a hole somebody had been digging at

one radioactive site.

Yet the main consequence of the end of the Soviet Union

was economic collapse. The Stans were left reeling, and

most people I met longed for a return to the financial

security of Communism. “At least we knew where we

were then,” said Kadyr Toktogulov, my Kyrgyz

guide.

Unemployment is now rampant in Central Asia; poverty,

censorship and government repression are the norm. As a

result, militant Islam is on the rise.

New groups are emerging in Central Asia which support

al Qaeda and could one day launch devastating terrorist

attacks on the West. American political support for the

authoritarian regimes in Central Asia is further

fuelling anger and hatred of the West and driving more

young men into the arms of new and established groups.

Heading south-west across Kyrgyzstan, an activist from

the shadowy banned militant Islamic group

Hizb-ut-Tahrir, which is becoming active across the

whole region, assured me “America will

die”.

Militancy has raised its head in Central Asia before.

In the 1990s the battered state of Tajikistan, the

poorest of all the former Soviet states, endured a

violent civil war between government forces and a

coalition of rebels and Islamic militants in which

between 100,000-200,000 died.

Now neighbouring Uzbekistan risks armed conflict.

Uzbeks are angry with their authoritarian leader Islam

Karimov and talk of revolution. In response tens of

thousands of militants and activists who oppose the

government have been tortured, jailed or executed. Many

have disappeared simply for being growing their beards

and being pious Muslims.

Militancy is not the only reason for us to take more of

an interest in Central Asia. The Stans are home to the

largest untapped energy reserves on the planet, and

international firms are battling for drilling rights to

exploit oil reserves in a replay of the 19th century

‘Great Game’.

Drug smuggling is also a massive problem in Central

Asia, much to the annoyance of the Tajik Secret Police

Colonel who guided me along the dangerous, porous

border with Afghanistan and fed me pilchards and a

prized bottle of vodka. Around 90 per cent of heroin in

Europe comes from Afghanistan, and much of that is

smuggled via Central Asia to Russia and the West.

On a drugs raid in Dushanbe, the Tajik capital, I

watched as the police seized a kilo and a half of

high-grade heroin from a mother of six. The police just

shrugged. It is a daily occurrence, they said, and

showed me a secret storeroom containing around 500kg of

captured heroin worth nearly as much as their entire

government budget.

Tragically, Tajikistan may become a failed

‘narco-state’ in the future. But the region

is so obscure, I fear few in the West would even

notice.

Copyright - Simon Reeve, 2004.

Simon Reeve is the author of The New York Times

bestseller The New Jackals: Ramzi Yousef, Osama bin

Laden and the future of terrorism, and the presenter of

‘Meet the Stans’, to be broadcast on CBC

from December 20-23rd at 8pm ET and 8pm

PT.

________________________________________

Buy Simon's latest book from here via Amazon:

The Daily Telegraph: "Pick of the Day…Heard of the Stans? Possibly not, but Simon Reeve’s tour of the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan should enlighten you. Reeve’s skill is in mixing the mundane with the serious, the shocking with the sublime, while an easy personality and various ‘fixers’ facilitate his travels and his discoveries"

The Sunday Times: "In an excellent two-part travelogue, the writer Simon Reeve explores four central Asian countries he calls ‘the Stans’. He is in the middle of nowhere, and so is the Beatles tribute band when he stops off in a small town after his truck suffers another puncture. Surreal images such as this abound, from camels grazing by rusting ships in a dried-up seabed, to white-coated women taking anthrax phials out of an unguarded fridge near an Islamic power base. It may look like another world, but, chillingly, it isn’t.”

The Globe and Mail (Canada): “Meet the Stans is a marvellous documentary series…Reeve is an utterly charming guide...it's all hugely entertaining. Meet the Stans is an absolutely enthralling set of postcards from the heart of Asia. The series is superb television. Reeve often plays the role of jolly tourist, curious about local habits and customs, but he's always got a keen reporter's eye for the telling detail that suggests more than surface reality. Apart from being great, absorbing entertainment, Meet the Stans is a thorough education.

The Age (Melbourne): “Simon Reeve wrote two bestsellers about terrorism, so his interest in the former Soviet republics isn't in finding a decent cup of coffee or a postcard view. He does a Palin-esque balancing act between the shocking and humorous, the mundane and bizarre. Funny, informative and scary.”

Sydney Morning Herald: “opens a window on a region dominated by oil, Islam, militants and enough radioactive waste to terrify the West.”

The Times: “Simon Reeve’s journey through Kazakhstan is a first-class Boy’s Own adventure on film and illuminating too. I can’t imagine anyone switching off who stays for the first five minutes.”

The Guardian: "Thrilling"

The Times: "Enlightening"

Evening Standard: "Fascinating"

The Observer: "Spectacular"

The Daily Telegraph: "Wonderful"

Radio Times: "Stan-tastic"

________________________________

Links:

Buying this series on DVD

Simon's Guardian article about the series

BBC article about the series

Series photos on Facebook

CENTRAL ASIA:

see the award-winning photography of James Reeve, Simon's brother, here

Disclaimer: The information on this website was as accurate

as possible when it was written, but situations change. We

accept no responsibility for any loss, injury or

inconvenience sustained by anyone resulting from this

information. You should conduct your own research before

traveling abroad and check for the latest information on

critical issues such as security, visas, health and safety,

customs, and transportation with the relevant authorities

before you leave.